Yale EEB lab puts prehistoric mystery meat to the test (spoiler alert: it’s not woolly mammoth OR giant ground sloth)

Sorry, Explorers Club, but woolly mammoth is no longer on the menu. Neither is the giant ground sloth.

A Yale-led analysis has shown that a famous morsel of meat from a 1951 Explorers Club dinner is not, in fact, a hunk of woolly mammoth. It is green sea turtle meat, most likely set aside from the soup course.

At issue is the taxonomic provenance of a fist-sized piece of animal flesh prepared for an Explorers Club shindig in New York City. The event, held Jan. 13, 1951 in the Grand Ballroom of the Roosevelt Hotel, featured a dinner of Pacific spider crabs, green turtle soup, bison steaks, and portions of a 250,000-year-old woolly mammoth that had been preserved in glacial ice. At least, that’s the menu that entered popular lore. Others in attendance at the dinner thought the main entrée was meat from an extinct giant ground sloth.

“I’m sure people wanted to believe it. They had no idea that many years later, a Ph.D. student would come along and figure this out with DNA sequencing techniques,” said Jessica Glass, a Yale graduate student in ecology and evolutionary biology, and co-lead author of a study published Feb. 3 in the journal PLOS ONE.

“To me, this was a joke that no one got,” said Matt Davis, a Yale graduate student in geology and geophysics, who is the other co-lead author of the study. “It’s like a Halloween party where you put your hand in spaghetti, but they tell you it’s brains. In this case, everyone actually believed it.”

Reports at the time said the Reverend Bernard Hubbard, a much publicized Alaskan explorer and lecturer known as the “Glacier Priest,” had supplied the mammoth meat for the banquet. The frozen beast allegedly had been found at “Woolly Cove” on Akutan Island, in the Aleutians, and shipped to New York by U.S. Navy Captain George Francis Kosco.

The banquet’s promoter, Commander Wendell Phillips Dodge, was a noted impresario and former agent for film star Mae West. He sent out press notices saying the annual dinner would feature “prehistoric meat.” Some attendees took this to mean woolly mammoth meat, while others believed they were being served meat from the giant ground sloth known as Megatherium. This was scientifically important, because although sloths extended into Alaska, Megatherium’s range was thought to be restricted to South America.

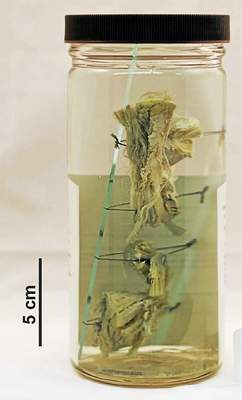

A club member unable to attend the dinner, Paul Griswold Howes of the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Conn., requested that a piece of meat be saved for him to display at the museum. Dodge personally filled out the specimen label for the fibrous chunk of muscle, saying it was Megatherium.

Yet over the years, the idea persisted that woolly mammoth had been served. The notion fit neatly with other stories in popular culture that imagined prehistoric mammoths found in blocks of glacial ice. That image remains iconic even today.

But science shows otherwise. Preserved mammoths would be found, not in ice, but in the frozen dirt of permafrost. “The meat wouldn’t taste good, but you could eat it,” Davis said.

This particular specimen, labeled as giant sloth meat, remained in the Bruce Museum until 2001, when it became part of the mammal collection at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

Eric Sargis, a Yale anthropology professor and curator of mammalogy at the Peabody, and a co-author of the study, grew increasingly curious about the sample. In 2014, Sargis found two students, Glass and Davis, who were interested in pursuing the true origins of the Explorers Club specimen.

Glass led the DNA analysis, and Davis conducted archival research. Both are members of the Explorers Club, which gave the Yale team access to its archives and provided a grant to support the study.

Adalgisa Caccone, a senior research scientist in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and a co-author of the study, helped guide the DNA analysis at Yale’s Institute for Biospheric Studies, Center for Genetic Analyses of Biodiversity. “This was an interesting challenge, in part because the meat had been cooked,” Caccone said. “This was the first time I looked at the DNA of leftovers — very precious leftovers.”

Glass was able to extract DNA, purify it and conduct mitochondrial gene sequencing. The results matched the genetic profile for green sea turtle.

Meanwhile, Davis found an item in the Explorers Club archives that pointed in the same direction. It was a published statement from Dodge soon after the banquet, joking that he may have discovered a “potion” that turns green sea turtle into giant sloth meat.

Beyond solving the origins of the Explorers Club entrée, the researchers said their study illustrates the value of interdisciplinary collaboration and the ability of modern science to use museum collections in new ways. Specimens can yield more answers than ever before, noted the researchers, making their preservation critical — even if they came out of a banquet hall kitchen.

“If this had not been from the banquet, we would still want to know the identity of the meat, because it would have large scientific implications,” Davis said.

Glass noted that this year’s Explorers Club banquet will be in March, but she’s unable to attend. “Maybe someone will save a piece of meat for me,” she said.

In addition to the Yale researchers, Timothy Walsh of the Bruce Museum was a co-author of the study.

External Links:

Center for Genomic Analyses of Biodiversity